Rebuilding the Ruins: David Rohl and the Courage to Trust the Bible

“If the foundations be destroyed, what can the righteous do?”— Psalm 11:3

For over a century, Christians have been told in no uncertain that the Bible cannot be trusted as a historical document. The stories of Joseph and Moses, of plagues and pharaohs, of conquest and covenant have all been relegated to the realm of myth. Not disproven, mind you: there is an assumption that these events are unhistorical because the timeline doesn’t line up with the “consensus” of modern Egyptology and Near Eastern archaeology. For Christians, that doesn’t matter. After all, “God said it. I believe it. That settles it.”

Such an attitude is commendable on the surface level, but it goes against the Biblical view of faith. In Christianity, faith is not turning away from facts but facing them with an underlying trust in God’s Word. This faith, for some, has been shaken by the academy. They have continually targeted one of the most bedrock events of the Old Testament and said, quite definitively, it never happened.

But what if the timeline itself is the problem?

Enter David Rohl, a man whose life’s work amounts to a single, piercing question: What if we’ve been looking in the wrong century all along?

This is Part One of a four-part series on how, when we take the Bible seriously as a historical document, we find not only theological riches but concrete historical truth. We need not be afraid of archaeology, ancient records, or scholarly claims. What we need is the courage to question the assumptions, especially chronological ones, that undergird most modern reconstructions of the ancient world.

Let us begin, then, with David Rohl: Egyptologist, historian, and chronological revolutionary.

Who is David Rohl?

David Rohl is a British Egyptologist and historian best known for his work challenging the conventional chronology of ancient Egypt and the ancient Near East. While not a Christian himself, Rohl is deeply sympathetic to the biblical narrative and argues that it has been wrongly sidelined in historical discourse because of a flawed Egyptian timeline constructed in the 19th century and rarely questioned since.

His work gained prominence in the 1990s with the release of A Test of Time (1995), followed by Legend: The Genesis of Civilisation and The Exodus: Myth or Histor?, which is both a book and a stellar documentary. In these works, Rohl argues that we should shift Egyptian chronology by several centuries. This is specifically due to shortening the so-called "Third Intermediate Period," a time when Egypt was ruled by invaders and the historical records become as clear as redacted government documents. If we do this, Rohl argues, then the result is a condensing of the Egyptian chronology and the biblical events of Genesis through Judges line up strikingly well with the archaeological and historical record.

Importantly, Rohl does not claim to "prove" the Bible in some simplistic way. Instead, he invites the reader to test the historical record without the bias of established but often fragile academic assumptions. He proposes that much of what we call “evidence against the Bible” is actually evidence for the Bible when placed in the correct historical context.

The Conventional Problem: Missing Persons

Let’s begin with the fundamental problem that sparked Rohl’s curiosity.

Open any mainstream archaeological commentary, and you’ll find a recurring theme: Joseph is nowhere to be found. Moses is a myth. The Exodus didn’t happen. Jericho fell at the wrong time, and the Israelites appear suddenly in Canaan with no signs of a conquest. So the story must be made up.

But what if we’ve been asking the wrong question?

Rohl’s proposal is simple but profound: What if those biblical characters are missing not because they never existed, but because we’ve been looking in the wrong era?

The current Egyptian chronology places the Exodus, if it happened at all, during the reign of Ramesses II in the 13th century BC. You can see this idea present in the classic movie The Ten Commandments, where Charlton Heston’s Moses faces off against this titular Pharaoh. This causes numerous historical problems. The records left by Ramesses’ reign are surpsingly unambiguous: there’s no sign of Egypt in distress, no wiped-out army, no mass emigration of slaves, and no conquest in Canaan that follows. So scholars conclude that the Bible is myth.

But the biblical record gives a much earlier date for the Exodus, around the 15th century BC (cf. 1 Kings 6:1). Mainstream chronology won’t allow that. It’s set in stone. Literally. And therein lies the problem.

The Revised Chronology: Shifting the Frame

Rohl proposes a revised Egyptian chronology that compresses the “Third Intermediate Period” (a time of Egyptian decline and chaos) by nearly 300 years. This is not a theological move. It is a chronological one, and one supported by many unresolved inconsistencies in the archaeological record.

This “New Chronology,” as it’s often called, results in a significant realignment:

The time of the Patriarchs shifts to the Middle Bronze Age, where we find Semitic peoples flourishing in Egypt.

Joseph appears in the court of a pharaoh named Amenemhat III, during a time when Semites had high status.

Moses is born under a later pharaoh (likely Dudimose II), during a time of national collapse.

The Exodus coincides with a period of massive societal disruption in Egypt—pestilence, famine, mass death, and sudden power vacuum.

Joshua’s conquest lines up with the violent destruction of cities like Jericho and Hazor—events that do not fit the Ramesside period but do appear centuries earlier.

Suddenly, the “missing persons” show up everywhere.

Joseph in History: The Man with the Multicolored Coat

According to the standard academic timeline, the figure of Joseph is untraceable in Egypt’s history. Rohl, with his revised chronology, makes a far more compelling, and visually dramatic, claim.

In the eastern Delta region of Egypt, at a site called Tell el-Daba (ancient Avaris), archaeologists have uncovered a vast Semitic settlement dated to the Middle Bronze Age, a timeframe which, under Rohl’s chronology, coincides perfectly with the life of Joseph. Among the finds at this site is a palatial structure, quite unlike the modest homes of the other Semitic inhabitants. It includes 12 tombs.

One stands out dramatically. This tomb was once pyramid-shaped, a rare honor for a non-royal individual, especially a Semite. But its most fascinating feature is what wasn’t found: the tomb itself was empty. The bones had been removed—a highly unusual practice in Egyptian burial custom, suggesting reverence or relocation.

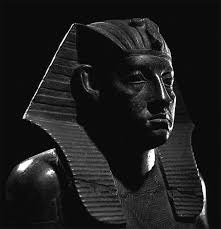

What remained was even more curious: a statue of the man buried there. The statue portrays a Semitic figure with reddish hair, pale skin, and wearing a striped, multicolored coat, a detail that immediately evokes Genesis 37:3, where Jacob gives Joseph a “coat of many colors.” No other known Semitic official has received such treatment.

Nearby, ancient records refer to a waterway in the area known as Pa-Ano (“the Waterway of the Son of the God”), but in a later period, it became known as “the Waterway of Joseph.” Egyptian records continued to refer to this canal by that name for centuries afterward, cementing the memory of a man named Joseph who fundamentally reshaped Egypt’s infrastructure.

The ruler under whom this Semitic man rose to prominence is identified by Rohl as Pharaoh Amenemhat III of the 12th Dynasty. Amenemhat was known for extensive building projects, including the reclamation of the Faiyum region through water engineering, perfectly aligning with Genesis’s portrayal of Joseph organizing grain storage and flood management during the years of famine.

Taken together—the empty tomb, the Semitic statue with a multicolored coat, the elevated palace, the name of the waterway, and the infrastructure projects of Amenemhat III—Rohl makes a compelling case: this is not just a Semitic official; this is Joseph, viceroy of Egypt, remembered in both Scripture and stone.

Moses and the Exodus: Catastrophe Remembered

In mainstream chronology, there’s no sign of an Exodus. But in the period Rohl identifies as the time of Moses, the evidence is striking.

Documents like the Ipuwer Papyrus (a Middle Kingdom text) describe a time when the Nile turned to blood, Egypt was in chaos, and slaves fled. Traditional Egyptologists date the document earlier than the Exodus, but Rohl argues that’s based on the flawed chronology. Reposition it, and the plagues come roaring back into historical view.

Additionally, archaeological strata show sudden abandonment and destruction of Semitic settlements in Egypt’s eastern Delta, consistent with a mass departure. Pharaoh Dudimose II, who ruled during this chaos, is one of the last kings of the 13th Dynasty. After his reign, Egypt collapses. Foreign rulers (the Hyksos) take over. It fits the biblical claim: “There arose a new king over Egypt, who did not know Joseph” (Exod. 1:8).

The Exodus doesn’t vanish from history. It is history. If you know where to look.

The Conquest of Canaan: Jericho Falls… Again

Jericho is the crown jewel of “Bible debunking.” Mainstream archaeologists point to the site and say: “There’s no evidence of destruction at the right time. So Joshua must be fiction.”

But Jericho was violently destroyed, just not in the Ramesside period. Instead, its walls fell centuries earlier in the Middle Bronze Age (around 1450 BC). That city was burned. Its walls collapsed outward. Grain jars were found full (indicating no prolonged siege). Sound familiar?

Rohl’s timeline places Joshua’s campaign shifts the archaeology up and places it exactly during this destruction layer. The biblical story and the archaeological data align—not myth, but memory.

Similarly, the city of Hazor, the largest in Canaan, was burned in a massive conflagration around the same time. The biblical account (Joshua 11:10–11) says Hazor was destroyed and burned by fire. Again, the match is uncanny.

What This Means for Believers

So what are we to make of this?

David Rohl is not a Christian apologist. He’s an agnostic. And yet his research may do more to restore confidence in the historical reliability of the Bible than a thousand well-meaning seminary lectures on “faith, not facts.” What he gives us is a framework, historical scaffolding, that allows us to take the Bible at its word. When we let Scripture speak and stop assuming that 19th-century Egyptologists were inerrant, we find that the Bible is not shy about history. It is history.

Rohl’s New Chronology is not without its critics. Many scholars find it too disruptive. Some claim it has too many cascading effects on other areas of historical study. Others point out that it is not yet widely adopted, and that conventional dating remains the norm.

But often, the strongest critiques are not of the data but of the implications. Rohl is asking the scholarly world to admit that it may have been wrong for over a century. That’s not just a question of evidence. It’s a matter of pride.

A Final Word: Faith and Courage

The Christian does not need David Rohl to believe the Bible. Faith comes by hearing, not by pottery shards. But it is still a good and noble thing to defend the faith against the slanders of modernity, and to rejoice when even the rocks cry out.

Rohl’s work reminds us that our faith is not based on clever mythologies or comforting fables. It is rooted in time, in place, in persons and events. The God who saved Israel from Egypt is the same God who raised Christ from the grave.

You are not irrational for believing that. You are not a fool for trusting that Joshua fought at Jericho and that Joseph interpreted dreams in Egypt.

What we need in this generation is the boldness to say: “Let’s question the assumptions and not the Scriptures.”

And perhaps, as we’ll see in the coming parts of this series, when we do so, we may discover that the Bible has been telling the truth all along.

Coming Up in the Series:

Part 2 – Re-dating Ancient Civilizations: A Flood of Clarity

Part 3 – What Bronze Age Collapse? Rethinking the Sea Peoples and the Trojan Legacy

Part 4 – De-Mythologizing History: Why the Bible Deserves the Benefit of the Doubt